Welcome to Startup ROI, where we explore global technology trends and how they manifest themselves in France 🇫🇷 . Whether you're an entrepreneur, investor or tech enthusiast, I'm glad to have you here!

This week, you are in for a treat. It's my very first collaborative piece with my internet friend and today's writing partner Ethan Corcoran. He's got a knack for articulating complex academic concepts, particularly in relation to UX design. We chose a theme for today's article accordingly. If you enjoy this piece, I highly recommend checking out his very own Substack, titled Turtles (All the Way Down!).

Designing Digital Communication - where to begin?

Where to begin?

A question I asked myself as I began preparing to write my segments of this article - not only is the subject area of digital communication both vast and complex in many ways, but I have also dedicated the past five or so years to researching this subject in both my academic and professional life.

I can take some solace, however, knowing that this is a question many others would have asked as the World Wide Web was being first developed. This technology and its protocols, developed by Time Berners Lee and a number of collaborators, is the framework through which all internet-based communication between people is able to occur.

The vast potential of this technology would have been as apparent then as it is now: a space where you can visually create almost anything and then share it with the world.

But where to begin?

I recently wrote an article which explores whether the use of analogue analogies for digital tools and spaces is helping or hindering digital innovation. Whilst there are arguments pointing in both directions regarding how these analogies impact the use of the Web today, there can be little doubt this was a necessary step in order to begin introducing people to the Web.

In the beginning, the ‘design’ of objects of communication in the digital and physical spaces were essentially the same. We had two broad categories of these objects physically: the ‘document’ and ‘mail’. For the sake of convenience, we will group the telegram with mail, for while the telegram was an important innovation, its ‘design’ as an object of communication was still modelled on the mail.

We can easily see these translated onto the Web as the ‘web page’ for a document and e-mail for mail.

This was incredibly useful for ‘onboarding’ potential users of the Web, and I need no citation to demonstrate its effectiveness, evident by the integral role this technology now plays in all our lives.

But, of course, the digital is not the physical. And where the digital excels, is inevitably where it would evolve.

Synchronising in Progress

Sending information through the internet is fast. Really, really fast. So fast, that you could send someone an email, and they could respond almost as quickly as they might in a real life conversation.

And so the ‘message’ was born. Arguably the first truly ‘internet-only’ artefact of digital design, the message combines the communicative function of the e-mail with the real-time interactivity of a live conversation.

I am aware I am probably explaining something you already know. The reason I do so, however, is because the obviousness of this progression can sometimes detract from how utterly groundbreaking it is.

Before the internet, there had never been any real form of innovation on the design of an object of text-based communication. We had the document, and the mail. For centuries. And then thirty-something years ago we just chucked the ‘message’ in and carried on.

How we, as humans, communicate is inextricably linked to how we socialise, a complex and fluid practice which is ever-changing and very fine-tuned, and closely linked with design. We can see this in real life, with fashion, jewellery and possessions (or a lack thereof) communicating just as much as what we literally ‘say’ to each other. We can also see this in documents and letters. We have very specific etiquettes and habits connected to these objects - we use titles, paragraphs, page sizes for documents. We introduce a letter with a greeting to its recipient(s), and we tend to sign both.

What the hell do you do with a message?

Just as a child learns to interact with the world through play, we started ‘playing’ with the message in similarly low-stakes environments. Early forums and chatrooms emerged online, and we started to tentatively explore this seismic addition to our social lives.

From this point of genesis, the message heralding the beginning of forms of communication only made possible via the internet, all aspects of our lives were set to change, and none less so than the professional space.

Because then we learned how to do a video call.

You've Got Mail

I have a vivid memory of the very first instant message I sent. It was the mid-90s and we had just installed our very first dial-up internet connection. We lived in a suburb outside of Chicago and created a space in the unfinished basement we designated the "computer room." We fired up the modem to an abrupt, ear-shattering — EEEEEE-OOOOO-EEEEEE-AAAAHHHH — that indicated we were, in fact, connecting to the internet. Minutes later, the dialog box appeared and I had to choose an AOL screen name: kyleob123. Seemed appropriate. Then I chose a password (likely of equal complexity) and came face-to-face with the magical place we call the internet. And then it happened. I clicked on the icon with the little yellow running man, called my uncle using a landline to confirm his screen name, and opened a chat window.

…Hello?

This was my very first online communication. Primitive but transformational. From there, my knowledge of the internet and the power of the internet itself expanded concurrently at breathtaking speeds. Chatting with friends online after school became a part of my regular routine. Soon after, it wasn't unusual to hop into chat rooms and meet "strangers" on the internet. In middle school, Facebook launched their offering outside of the university system and suddenly we attributed real, identifiable information to our online personas and evolved from basic conversations to creating metadata, commentary and threads. The mobile era only accelerated adoption and ensured that we were in constant communication at virtually all times. So it's no wonder that an online generation precipitated the rise of the "social enterprise" -- fusing personal habits around real-time communication and knowledge sharing with the workplaces we now inhabit.

That said, the social path to the enterprise wasn't clear cut and certainly wasn't smooth. I still remember an early internship where I got set up with IT and opened Lotus Notes for the first time. I remember encountering internal communication issues that seemed easily solvable if we just applied standard consumer internet techniques to our team's approach to collaboration. I recall thinking how ironic it was that a company that prides itself on efficiency, productivity and performance (and goes to great lengths to measure it) was missing out on the biggest opportunity to harness collective knowledge, enable good ideas to bubble up from below, and ultimately impact the bottom line. Inevitably, this happened, albeit with a variety of tools and various products over the years. For a long time, productivity tools were either built in-house or the startups working to solve the problem were acquired by large, enterprise companies as a way to differentiate (not to mention these startups hadn't quite figured out how to monetize their innovation). Let's break down this first era of enterprise collaboration and productivity, a time where startups were gobbled up by the big fish, the term social enterprise was scoffed at, and the precursor to modern collaboration tools made its way into public consciousness.

A Bumpy Ride

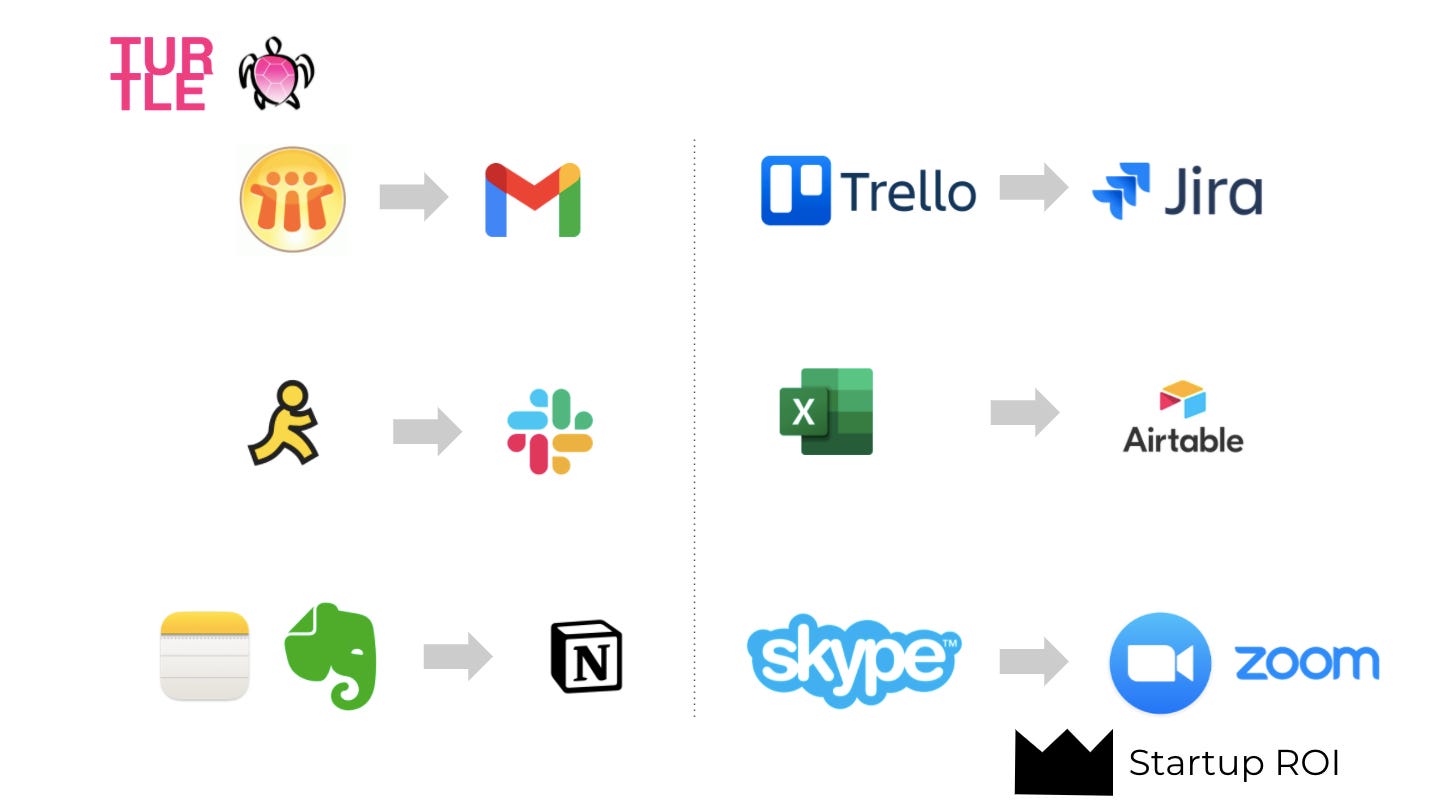

Circa 2012 onwards, and the dust has started to settle (as much as it can in the digital age) to reveal the landscape of digital collaboration and communication for professionals.

As far as collaboration of the synchronous kind was concerned, you had direct messaging and video calling, and that was essentially the ‘suite’ available.

Over time, we started to see more task-managing solutions introduced such as Trello, but the real ‘activities’ of digital collaboration essentially broke down to messaging and online calls.

And unless you’ve been living under a rock for the past eighteen months, you are probably aware that these methods of collaboration may have some underlying issues.

You have probably seen a number of articles cite the term ‘Zoom fatigue’ or discuss the issues of direct messaging and the ‘always available’ professional culture it has generated, but these topics do little to better understand the underlying reasons why these means of communicating create such problems.

Let’s step back from the technology for a moment. Here is a quote from the first page of Albert Wittgenstein’s Philosophical Investigations, first published in 1953:

"When they (my elders) named some object, and accordingly moved towards something, I saw this and I grasped that the thing was called by the sound they uttered when they meant to point it out. Their intention was shewn by their bodily movements, as it were the natural language of all peoples: the expression of the face, the play of the eyes, the movement of other parts of the body, and the tone of voice which expresses our state of mind in seeking, having, rejecting, or avoiding something. Thus, as I heard words repeatedly used in their proper places in various sentences, I gradually learnt to understand what objects they signified; and after I had trained my mouth to form these signs, I used them to express my own desires."

— Ludwig Wittgenstein (G.E.M Anscombe), Philosophical Investigations, 1953

Wittgenstein here is quoting Augustine, who wrote this in his ‘Confessions’ in circa AD 400.

I find this quote fascinating because it demonstrates how deeply rooted our ability to communicate is to the environment we communicate in.

What I mean by that is, the way we use language and learn to use language, the same today as it was for Augustine, is through the relationship between words and the real objects in the world they represent.

You could argue that language never works better than when you have something to ‘point at’, as Augustine’s elders did for him.

What is different between now and AD 397 (well, one thing that is different) is that we also have the digital environment as well as the physical.

And in the digital, you have nothing to point at.

A name I will give to this concept of ‘pointing at’ is ‘shared context’. We are building a house. I need you to pass me a brick. I say ‘pass me the brick’ and point to the brick. You see the brick. You pass me the brick.

In this instance, the brick is our shared context.

We find it challenging to communicate online through direct messages and online calls because it isn’t how we learned to use language. It’s almost like having only half your vocabulary to work with. This goes some way to explaining the phenomenon of ‘Zoom fatigue’ and the long list of articles concerned with the intricacies of message-etiquette such as how many ‘ha’s’ to put in a laugh.

But a new world is forming. Remote work is a much more serious prospect for companies around the world, and many teams are becoming more and more spread out via location and timezone. We can no longer put up with these digital shortcomings for communication.

Digital communication needs a new design.

Inertia in the Enterprise

There are two key dynamics in this era that I find particularly interesting:

The first is adoption of social/consumer-style tools by the Enterprise

The second, is the viability of these early tools as stand alone products. The ensuing skepticism, optimism, acquisition cycles and products replacing the "irreplaceable" is quite a trip.

Evernote: The Elephant in the Room

Let's start with an early mover to the "productivity" scene: Evernote. Described as note-taking and task-management software, it provided an early (and eventually, cloud-based) alternative to something like Microsoft Word. For highly organized researchers & note-takers, there were some advanced features that enabled archiving, organization & enhanced formatting. But for the general public, the difference was hardly noticeable. They must have been one of the first internet startups to adopt a freemium model, whereby app usage was free up to a certain data storage limit where you paid a modest monthly fee. With a majority of users under the free plan and a few die-hard paying customers, the challenging economics start to become clear. Though slightly better than what's available today, most users are not willing to pay for the service. In addition, the rise of Google Docs provided a free competitor that sits squarely in the existing user workflow for G Suite users (same with Notes for Mac users).

However, if you put that in the context of the enterprise, the dynamic changes pretty quickly. And so do product requirements. The first advantage: large companies have a budget for tools like this. Not only that, but they have a huge incentive to invest in a single tool used across teams that is searchable, shareable, and collaborative by nature. This pivot from user-focused to Enterprise ready became the model for many early productivity apps. Later, the playbook to the enterprise via user-focused early adoption would become standard.

Salesforce's Chatter: Shark Teeth

Thinking back to the early years of social media, it's hard to imagine companies like Facebook as the "underdog." At the time, it wasn't obvious they could monetize. Today, they are a behemoth advertising machine with nearly 3B monthly active users. You might also recall that the power of social media as a brand building mechanism was misunderstood (or flat out denied). Social Media Management was outsourced to college interns who just get how to use the damn thing. While the rise of internet culture, influencers and performative social media accounts received plenty of eye-rolling, the next generation of consumers was being primed to adopt new online behaviors and expectations. Large companies simultaneously mocked millennials while desperately searching for a way to connect with the incoming class of university graduates accustomed to streamlined, conversational interactions on the web, and ultimately in the workplace.

One of my favorite examples of forward-thinking that was not well-received by critics in the tech community was Salesforce's announcement of Chatter, it's embedded feed within their CRM interface.

"Who needs Facebook at work?

It's going to be a distraction!

You call this productivity?"

Benioff revealed it at Salesforce's annual Dreamforce event to crickets. The reality is, they were ahead of their time, but eventually the idea took hold. Social tools are inherently "social" but that doesn't necessarily mean distracting or unproductive. Using an @mention on a Sales Opportunity to notify a teammate or tagging Leads with information you could later query in your reports and dashboards was completely logical and in fact visionary. But once again, the company they acquired, likely wouldn't survive independently. It needed to be nested within an enterprise application that could support it. I think of it like a symbiotic relationship between a shark and a cleaner wrasse (fish). Why might this tiny fish enter the jaws of a top-tier predator? The little fish feeds off the extra food stuck in the shark's teeth. In exchange for their service, the shark doesn't swallow them whole.

Death to Excel, Long Live Excel!

If there is one tool that might be considered irreplaceable, it's Microsoft Excel. It's the backbone of the modern enterprise. And while that's changing, new age competitors typically try to build something adjacent or use-case specific. There are very few companies that would endeavor to re-invent Excel. If it ain't broke don't fix it. Nevertheless, someone tried and succeeded. That's not to say Excel is obsolete (far from it!), but the fact that a company like Airtable can go head to head with an Enterprise mainstay and dominate the market shows that the way we work and our product expectations are vastly different than they were just 20 years ago. Not everyone is an excel wiz, and many users would gladly take the diet excel in exchange for a better user interface, enhanced functionality, and of course, baked in collaboration tools. Which is exactly the approach Airtable took. Forget macros, create a visual workflow. Who remembers every formula? Let's make it simple for the masses. Saving updates and sharing an attachment via email 100x? Let's put it in the cloud and layer in chat capabilities.

These three (mini) case studies illustrate some powerful concepts that have influenced trends permeating the productivity & collaboration ecosystem today:

Individual consumers tend to be a point of entry, but the Enterprise is the end goal to achieve sustainability and widespread adoption

Consumer social is no longer just for consumers, social media has rewired our approach to work, collaboration and productivity in the workplace

There is always room for new ways to collaborate, nothing is set in stone. Cultural (social media), technological shifts (cloud computing) and exogenous events (Covid-19) alike drive fundamental changes that leave room for new entrants, no matter how much established incumbents appear to have a vice grip on the market

What's Normal, Anyways?

In the advent of Covid-19, the early precedents for collaboration and productivity software can be thrown out the window. Everything has changed. At the risk of repeating every tech newsletter writer on the internet: current tools for collaboration and productivity simply weren't designed for a 100% distributed workforce. There's a difference between pivoting a business trip into a Zoom call to save time, money and the environment; but when it comes to 8+ hours a day on video conference, you end up with all sorts of new health disorders (see: Zoom Fatigue). For a while, there's been an active camp on Twitter (and elsewhere) touting their vision for the future of work. But recently, it's come barreling into the mainstream in a near comical fashion.

The premise is simple: will we ever go back to the office? There are proponents on both sides, but we find ourselves at equilibrium somewhere on the spectrum of hybrid. That is, a mix between working from home, the office and in some sort of virtual or augmented reality. The futurists will pitch you some Ready Player One vision of the metaverse where as more conservative speculators talk a big game about home office ergonomics. But for my portion of this section, I want to continue with the theme of collaboration and productivity and how it will evolve in a highly distributed work environment. In the French tech ecosystem, I've encountered two startups working to pull it off. And to do so, they not only have to reckon with the challenges of building a company in the current climate, but entirely rethink the way their product facilitates collaboration in this brave new world.

From my vantage point, there are two approaches to building solutions for the future of work (and they just so happen to mirror our original onboarding to the internet). The first, is to take physical properties of the office/meeting culture/collaboration and digitize them. The second is to redesign workplace collaboration from the ground up to accommodate the movement towards highly distributed workforces. In my mind, both approaches make sense. The on ramp to fully remote will require some muscle memory from the olden days when we commuted to the office and bumped into colleagues at the water cooler. But there are without a doubt, certain motions that either cannot or should not be replicated at a distance.

First up: Klaxoon. I first encountered the app during a brainstorming session in which a clever developer initiated and shared a space for everyone to contribute ideas that we subsequently arranged, modified and shaped into a formal project plan. It was the closest thing I've encountered to a digital-first design thinking session. As it turns out, this functionality only scratched the surface. The company is championing what they call the "meeting revolution" -- taking ordinary meetings and up-leveling them with digital and physical tools to make them more productive and engaging and to generate better outcomes.

The company raised a €5M Series A in 2016 that was quickly followed by a €50M raise just 2 years later. Their product suite expansion is commensurate with the multiple on their Series B. The digital whiteboard served as a starting point for surveys, kanban boards, async communication tools, and even hardware (the Klaxoon box & meeting board). While they've got one foot in the physical world, they've made their intentions clear: hybrid work is the way of the future.

There are innovative companies and then there are category defining companies. According to Pierre Touzeau, their co-founder, Claap aims to be the latter. Many companies are retrofitting their products for the remote workforce, but only a handful (for the time being) are emerging in this era of fully distributed work, presenting them a unique opportunity to start from scratch. Claap is combining lessons learned from before, during and after the "transition" to build something that's flexible enough to adapt to every team's needs but prescriptive enough to rewire our approach to collaborating with teammates from anywhere and at any time. They've identified a solution and are in the process of evangelizing their blueprint for the future of work.

For Claap, the real enemy is Zoom fatigue and back to back agendas. Boring meetings lead to unproductive outcomes, decreased engagement prevents decision-making, and our isolation-induced blurred sense of time makes us forgetful, not to mention lost between context switching. Which is why in-situ, asynchronous collaboration paired with decision logs and productivity tools seems to bring the best of all worlds. To illustrate, here's a screen grab of Pierre walking through the Startup ROI website with Claap running in the background. He can select any space on the page to add a context layer and assign to another user with deadlines and calls to action. When I open up the Claap later on, each comment will be demarcated on the screen with a built-in feed for continued discussion.

It should be noted that Claap itself is a remote-first company. They're drinking the remote-first Kool-Aid and should things go according to plan, they'll be serving it too.

Look to the Horizon

Companies like Klaxoon and Claap are proving that software which seeks to explore digital-first collaboration that reimagine the workspace are able to succeed, but what does the future hold from here? Will we continue this trend and use the unique properties of the digital for a future of work that builds on, and moves on from, the past? Or will we keep using the digital to simply replicate it?

So, Facebook launched its new VR workrooms application ‘Horizon’ this mid August.

It seems only apt to start here when considering the ‘future of work’. I think Charlie Warzel summarised the announcement of Horizon perfectly in his excellent article with a sense that is best described as ‘wariness’.

Zoom-ception, anyone? I thought not.

To go all the way back to the start of this article, I talked in my first section about how we were ‘onboarded’ onto the Web through the use of physical analogies, so that we could get a foothold on the Web and make some use of it.

Facebook would appear to be employing a similar strategy here. They want people to get used to the ‘metaverse’ as it is being called, the virtual universe that VR can create.

But nobody wants them to do that. And furthermore, there’s really no need.

The analogy worked great back in the nineties, nobody is questioning that. But now these physical analogies are just limiting the potential of the digital, and it’s time we start to push the boat out on not just being as good as the physical, the analogue, but finding a new, better paradigm for work.

And we already are. Anthony Tan and Jasmine Sun wrote a very insightful article recently comparing the development of the free VR platform VRChat and Facebook’s Horizon. The ability for users to design their own virtual environments in VRChat have led to extraordinary creations nearly impossible to imagine, and consequently social interactions we never thought possible.

Just as messaging began in the social space, so too is VR in its early stages flourishing there, where its development isn’t owned but shaped collectively.

The workplace we left behind when COVID began wasn’t one many remember kindly. This fact shouldn’t need citation, but for the sake of getting the point home we need not look further than the recent unveiling of the professional culture found at games company Activision Blizzard to know the workplace as we knew it has never been ‘for’ everyone.

Do we really want to let Horizon take us back there, when for the first time, we could go anywhere?